Dudley’s Female Computers

Dudley Observatory has spent most of its 160 years as a working science institution, and not a museum. That means that its employees weren’t always focused on saving the kind of materials that a museum would preserve. Of course, they saved the astronomical materials they were working with, but not always the bits and pieces of their own history that would be so interesting today.

Which explains why we have so little about the staff of Dudley itself. Even from Dudley’s height, about 1905-1935, there are only two staff photographs. One of which survives only because it was used as a bookmark.

Here’s one of those photographs, taken at the South Lake observatory, around 1915:

Middle: (kneeling): Miss Isabella Lange, Miss Alice Fuller

Front: Misses Mary E. Bingham, Florence Gale, Bertha W. Jones, Mabel Aline Dyer]

One thing you’ll notice: out of the fifteen people here, nine of them are women. Since Dudley is usually associated with male astronomers – like Benjamin Gould or the Boss family – what are these women doing here?

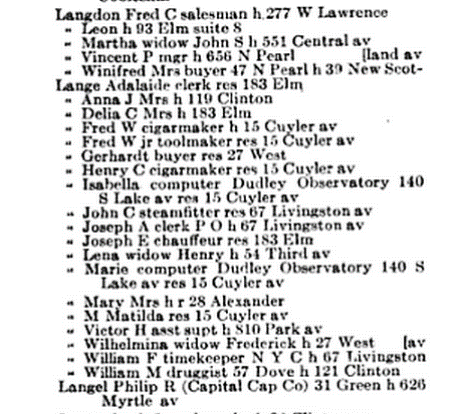

They were doing what women had done in the field of astronomy since Caroline Herschel became the first female professional astronomer in the 18th century: mathematics. The Dudley was focused on creating a star catalog, which meant recording the exact positions of stars in the night sky. Fixing these positions required massive amounts of computation. Observations had to be run through a tricky statistical equation in order to get the most accurate possible result. At the time, the people who did this kind of work were called “computers”, and for a variety of reasons we can get into later, they were frequently women.

The director of Dudley, Lewis Boss, started the process, and when he died in 1912, his son Benjamin Boss took over. Their ambition was to create the largest and most accurate catalog of its time. It would ultimately include over 30,000 stars. This required so many computers that little Dudley Observatory in the sleepy town of Albany became the largest employer of women in American astronomy during the period that that catalog was in the works. In total, they employed 81 women during this period between 1900 – 1940.

In other times and places, women computers in astronomy would go on to become notable astronomers. Alas, not at Dudley, where the limited scope of work and limited resources didn’t allow women to branch out. Just as frustratingly – at least for us – Dudley didn’t collect any personal material from these women. I can tell you who was on Benjamin Boss’ Christmas card list, but not what Isabella Lange thought of her career in astronomy.

So, a personal appeal: if you happen to know anything about the women in the photograph above, or any other of Dudley’s female computers, please drop us a line at: counting.stars@dudleyobservatory.org .