“A Deed of More Perilous and Romantic Courage has Perhaps Never Been Undertaken …”

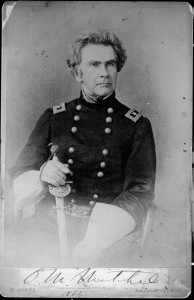

Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel was a tireless scientist and engineer who deserves a share of the credit for shaping American astronomy. He was an institution builder and a self-taught astronomer responsible for starting both the Cincinnati Observatory and our own Dudley Observatory. He was also an inventor, and his chronograph allowed a single astronomer to both make observations and record the exact time the observation was made. This made the star catalogs late 19th century possible.

But for all that, Mitchel is likely to be best remembered for something that has nothing to do with astronomy.

Mitchel helped found the Dudley Observatory and became the director, but he never set foot in the building. That’s because the Civil War started before he made it to Albany. Mitchel entered into the Federal Army with a reserve rank of brigadier general and organized defenses around Cincinnati, Ohio, then moved into Kentucky and Tennessee.

It was in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in April of 1962 that Mitchel saw an opportunity. He was not far from rebel-held Chattanooga. He could take Chattanooga, but there was a rebel held railroad running from the city down to Atlanta, Georgia, that would bring up rebel reinforcements. But if that railway was somehow destroyed, then Mitchel could hold Chattanooga and win a major victory.

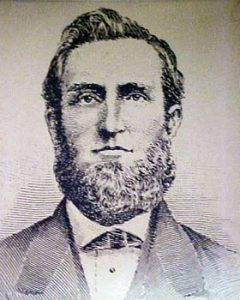

Mitchel didn’t have the troops to attack both Chattanooga and the well defended railway. That meant it was time to get sneaky. Mitchel worked out a plan with a civilian spy named James J. Andrews. The agent would lead two dozen Union soldiers in plain clothes down to Atlanta. There they would steal a locomotive engine and flee back towards Chattanooga, destroying the railway bridges as they went. Then they would shoot through Chattanooga and rejoin Mitchell’s army.

The plan started off without a hitch. Andrews and his men slipped into Marietta, just north-west of Atlanta. Meanwhile, Mitchel successfully took Huntsville, Alabama, which would be Andrews’ destination after the operation. Two of Andrews’ men were accomplished engineers, and they slipped into an unattended train named The General, uncoupled it from the baggage cars and steamed off with their stolen engine.

Things fell apart not long thereafter. Despite their haste, they were required to sit for twenty minutes on a side track to let another train pass. This was enough time for the rebel troops in Atlanta to figure out what had happened and set off in pursuit with their own engine. Andrews and his men had to abandon the plan and steam ahead as fast as possible to escape their pursuers.

What followed was a hundred mile railway chase which has become legendary in American history. Dubbed The Great Locomotive Chase, it captured the imagination of the American public. The popular historian John Stevens Cabot Abbot wrote a breathless article about the raid for Harpers in 1865 from which I took my title, “Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men.” It has been the subject of probably a dozen books, starting with Daring and Suffering by one of the participants, to the recent Stealing the General by Russell Bonds. It was the inspiration for Buster Keaton’s 1926 movie “The General,” and in 1956 it became a Disney movie starring Fess Parker (AKA “Davey Crockett”) as James Andrews.

The Disney film got mixed reviews, likely because the ending was downbeat. Andrews and his men ran out of fuel and had to abandon their engine. They were rounded up and imprisoned. Eight, including Andrews, were eventually hanged. Their mission failed, and Mitchel did not take Chattanooga. He would die six months later of yellow fever.

The bravery and ingenuity of the men involved has not been forgotten. When the Medal of Honor was created in 1863, one of the raiders named Jacob Parrott became the first recipient. Unfortunately, James Andrews himself could not receive a posthumous awards since he was an espionage agent and not officially part of the military. He is remembered on a monument at the Chattanooga National Cemetery.