How to Measure a Mountain Without Leaving Your Observatory

Nineteenth century observatories were more than just places to look at the stars. They were packed with scientific instruments that were useful for all sorts of purposes: highly accurate clocks, barometers, thermometers, transits and other surveying equipment, and so on. Many observatories were staffed by people eager to reach out to the public, either as part of their mission or to justify their funding. Observatories could become little temples of science for their community.

As a rare privately funded observatory unattached to a university, Dudley had (and has) a strong need to be useful to the community which created it. I’ve mentioned Benjamin Gould’s plan to provide accurate time for New York. Since time is a measure of the earth’s rotation, the observatory could help mapmakers determine longitude. Dudley also offered public viewings to all, right through the Civil War.

Here’s one interesting example of Dudley making its scientific resources available. In 1870, the naturalist and engineer Verplanck Colvin was working on a geological survey of the Adirondack region. As part of this project he completed the first recorded ascent of Seward Mountain. To complete his survey, he needed to know roughly how tall the mountain was.

One way to work out the height of a mountain was to take barometric readings at the top. Since air pressure is lower the higher you climb, you can compare those numbers with readings taken from close to sea level. By working out the difference, you can figure out the difference in elevation.

For the best accuracy, the readings should be from the same region and at the same time. But synchronizing time can be a little tricky when you’re on the side of a mountain. Fortunately for Colvin, in 1870 the head of the Dudley Observatory was George Washington Hough.

Hough was not only an astronomer, but also an inventor. And his pride and joy was a self-reading and printing barometer, which could keep track of changes in the barometric pressure and keep record of when they happened. So when Colvin came down from the mountain, he could send his notes to Hough, who would compare Colvin’s readings with his own records from the appropriate time.

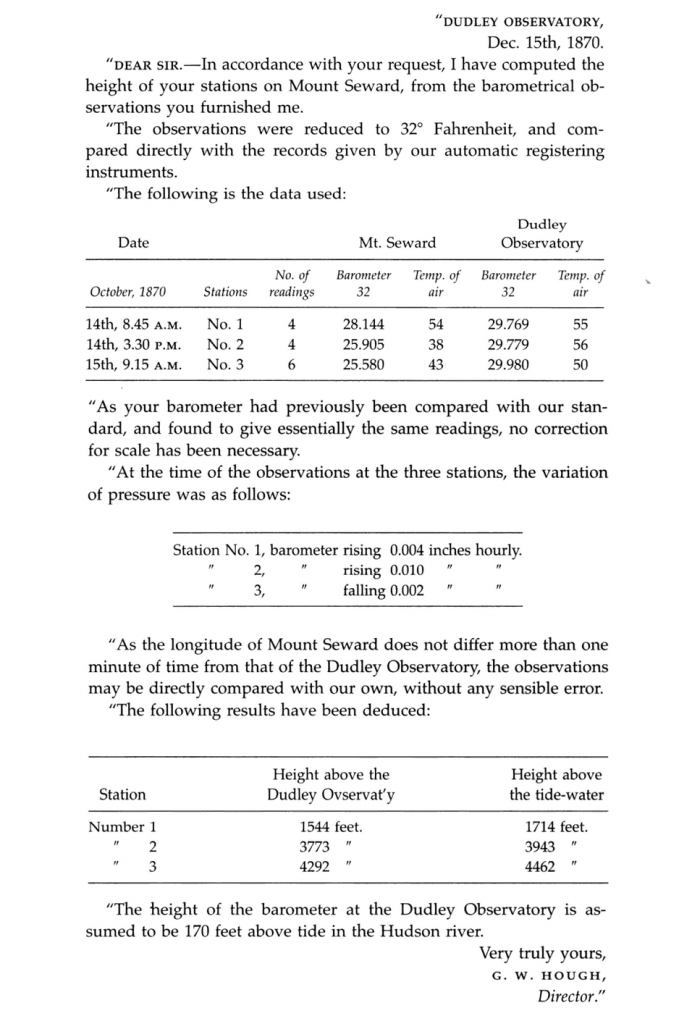

Colvin took the results and presented a report at the Albany Institute. Fortunately for us, he included the text of the letter he received from Hough:

The result was significantly lower than previous estimates, but not far off of the current measurements. It’s a small thing, but it helped establish Colvin as a serious surveyor and helped him gain funding for his continued work in the Adirondacks. And that is important for New York, because Colvin became the father of the Adirondack Park.

Immediately after this presenting this letter, Colvin began to describe the damage caused by lumbering that he had seen from Seward Mountain. He proposed that the Adirondacks become a state park to protect the forest. He cleverly tied the preservation of the forest land, which shielded lakes and snow packs, with the need for water in the Erie Canal. It became a major theme of his work. When he was later appointed the superintendent of the New York state land survey, he oversaw the creation of the Adirondack Forest Preserve in 1885.