No Longer in the Collection: Scheutz Difference Engine

Of all the instruments that Dudley has used throughout its century and a half of operation, the one that most stands out is the Scheutz Difference Engine. Although it is now housed in the Smithsonian, the Scheutz served Dudley well for the first half of its life, and it allowed a small observatory with limited staff to operate at a much higher level.

The Scheutz Difference Engine was created by the father and son team of George and Edvard Scheutz, two Swedish publisher and inventors inspired by the notes of Charles Babbage. Babbage himself had been unable to complete his design, supposedly because he could not get parts made to the necessary precision.

Babbage may have been ahead of his time, but not by much. Babbage sketched out his designs in the 1820s, and George and Edvard were able to create a very basic model by the late 1830s. Thanks to a grant by the Swedish government, the father and son were able to design and create a full scale difference engine by 1853.

The Scheutz family put the working difference engine on display during the Paris “Exposition Universelle” in 1855. One of the five million visitors was Benjamin Gould, traveling through Europe in order to acquire a telescope for the new Dudley observatory. A friend of Charles Babbage, Gould was impressed by the engine and bought the first available model.

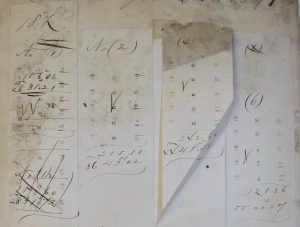

The engine was crank operated. By turning the handle – seen on the left side of the image above- a sequence of wheels and gears would turn throughout the machine. The engine had four banks of number wheels with fifteen wheels each. As the wheels turned, the settings on these wheels were run through what amounted to an adding process. The results were displayed on one set of the number wheels and also printed out on a slip of paper.

Scheutz Engine Print-outs

That last bit was a leap forward. Charles Babbage himself had been unable to get a machine to print, but the Scheutz family managed a working solution. Here at Dudley, astronomers kept notebooks of their calculations. When working with the the Schuetz engine, the astronomers just pasted the print-outs into their notebooks and marked them up as part of their calculations. While we no longer have the engine, we still have many of these notebooks, which are now probably the oldest computer print-outs surviving.

While the Scheutz Difference Engine was an incredible achievements, it had its issues. While it was a great proof of concept, it simply wasn’t reliable enough for constant use. The usefulness of the engine was directly proportional to the technical ability of the person who had to fix it: Benjamin Gould could keep it operating, as could his successor George Washington Hough, but Lewis and Benjamin Boss could not get it working. The machine was sold to Dorr E. Felt, inventor of the comptometer, in 1924. Felt and some of his fellow inventors were able to keep the engine working and put it on display. In 1963, Felt’s collection of early computers was donated to the Smithsonian. The Scheutz Difference Engine is now part of the National Collection and is sometimes on display at the National Museum of History.