The Battle of the Board

It’s an unfortunate fact that the Dudley Observatory, no matter what it has accomplished and no matter what it may accomplish, will always best be known to historians for its near collapse just as it got started.

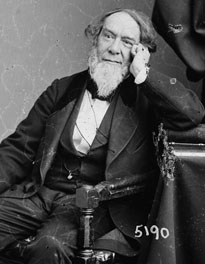

The simple version of the story is that a split occurred on the board not long after Dudley was founded. On one side was the Scientific Council, made up of the scientific advisers along with the first director, Benjamin Gould, and his patron Alexander Dallas Bache. On the other side were the Trustees, the financial backers like Thomas Olcott and Dr. James Armsby. The two sides argued, in person, in the press, in the backrooms and in the courtroom, until Gould was forced to leave. People all over the nation followed the arguments, and still today the fight is studied by historians of American science.

Figuring out what the argument was about takes some work. Anyone familiar with board fights, or internet arguments, can probably guess the arc: everyone started out as friends with a polite disagreement, and by the end everyone else was the antichrist. Both sides had long and well-practiced lists of complaints about the other.

Reading between the lines of those lists, it looks like the Scientific Council and the Trustees had different visions of what Dudley would be. The Council wanted a top notch scientific institution that would do serious science and nothing else. The Trustees, representing the people who put forth the money, wanted an observatory that would serve the Capitol Region, both by doing useful science and by adding luster to the city’s reputation.

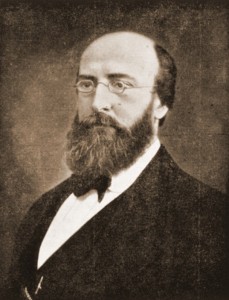

Alexander Dallas Bache (1806–1867), director of the Coast Survey

These goals were not incompatible at first. But in 1857, while the observatory was still incomplete, a financial crisis made money tight. That meant one side or another would not get their vision of the observatory. The Scientific Council thought that the observatory should be shut down until sufficient money was raised to run it properly; better to let it sit unused than do poor quality work. The Trustees wanted the observatory to start work with whatever equipment it had, to serve the public that had footed the bill to construct it.

The details of the arguments that followed would fill a book (specifically, that book is Elites in Conflict: the antebellum clash over the Dudley Observatory by Mary Ann James). All of that is something to cover at another time. For this post, it’s probably best to ask: why should anyone care? With the exception of us poor souls who are paid to care, why should this interest anyone?

American science was in a transition that would take it out of the hands of gentleman hobbyists in the early part of the 19th century and leave it with professional scientists by the end. This process, called the “professionalization of science,” turned science into a job, created familiar scientific institutions and granted scientists the social authority they have today.

At the center of this process was Alexander Dallas Bache. Great-grandson of the ultimate gentleman scientist, Benjamin Franklin, Bache nevertheless worked towards a vision of science that would make his ancestor’s career impossible. Some historians say that Bache did for American science what FDR did for American government: reorganize it on a much grander scale. Bache was well connected, shrewd and (usually) diplomatic, and he was firmly in support of his ally Benjamin Gould and a Dudley Observatory run along professional lines.

And he failed. It’s one of the few times he did so, which is part of why it’s so interesting. The Battle of the Board sits right in the middle of several of the major disputes of professionalization: how to pay for the new science? How to organize a scientific institution? Who should be in charge? By following the arguments we can get a sense of what forces were at work in this large and important transition.